In the cave of Patmos, where John the Theologian is said to have seen that fearful Apocalypse, is set up a certain majestic icon, almost having a man’s size. This icon, “The Vision of John” inscribed, is the work of Thomas Vathas, a Cretan painter of the late years of the sixteenth century, who around 1599 ended his life. Our discourse here is not about religion, or about the nature of visions—for these things to the theologians we leave—but about the artefact itself, of the wood and of the colours and of the art which the artist employed. This art, the so-called Cretan School, was of a peculiar character; for it stood always in a borderland, holding fast to the old Byzantine dignity, but stretching out a hand towards the innovations of the West. Vathas therefore, mixing tempera with egg upon wood and placing a gold background, not only did he imitate the ancestral [ways], but also the German engravings, of Dürer I say, he greatly admired, as they say, and incorporated into his Byzantine composition. This work, having 170 centimetres height and 116 width, having been commissioned specifically for the Cave, not only does it show theology, but also that complex history of Venetian-ruled Crete and of its artists, who brought together east and west.

Twofold composition and mixed art

The composition of the icon is immediately divided into two levels, the lower earthly place and the upper heavenly [one], like a two-part theatre stage. Vathas follows indeed the Byzantine order, but each part he works with a separate art.

The lower world; the prophet in ecstasy

Seeing the icon, we behold John below indeed, having a bare head and a halo, lying upon the earth of Patmos. Not as sleeping simply, but as enraptured, possessed by the divine spirit, he appears, reclining his body and turning his head towards the vision. He wears a green chiton indeed, and a crimson himation, colours customary in Byzantine art for the evangelists. This posture, this reclining, is not new; it is drawn from old prototypes, from the Byzantine manuscripts, I say, which showed the prophet resting or writing on a mountain. Vathas here remains faithful to the tradition of the art. His face, being old and venerable, denotes the perplexity of the man before the divine vision which is unfolding above his head.

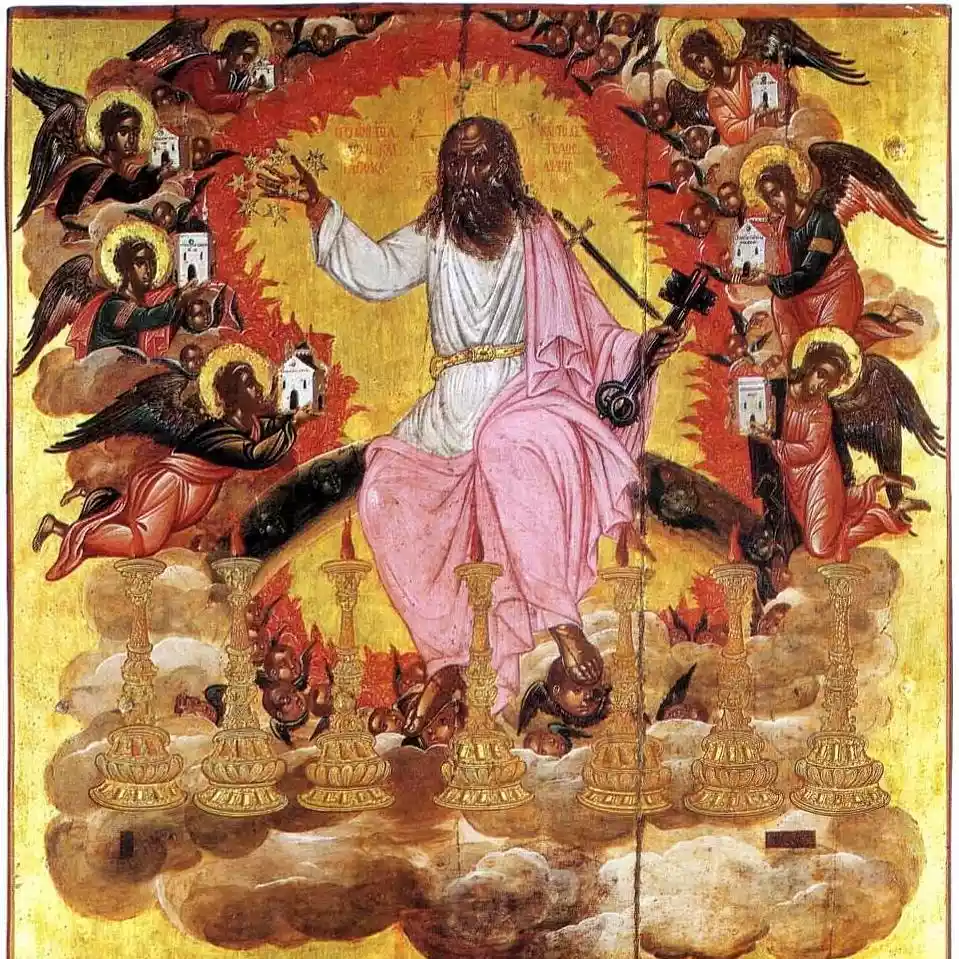

The upper vision; the Christ and the Seven Churches

But above all the wonder of the Apocalypse erupts. In the midst is Christ, not as the humble Nazarene upon the earth, but as the “Ancient of Days” of the prophecy, enthroned upon clouds of fire and of golden glory. And He has a rosy himation and a white chiton—the painters of Crete thus often hinted at the double nature, both divine and human. But look now. This form, although venerable and Byzantine, is not devoid of Western ways. The way in which the folds of the rosy himation fall, showing the fabric heavy and monumental, and the solid stance of the body, reminds us… yes, of the engravings of Dürer. That German artist, having engraved the Apocalypse, was a great wonder everywhere, and indeed also in Crete, and Vathas appears to be borrowing from here. And around Christ are all the symbols of the book; He holds seven stars in His right hand, a two-edged sword proceeds from His mouth—a certain fearful spectacle truly—and seven golden lampstands, the seven churches, stand before Him. And encircling Him are angels, not only winged heads (and this comes from Italy, from the Renaissance), but also full-bodied angels bearing small edifices, like temples; and these, as is likely, signify the seven churches of Asia, to which John is about to write. This icon of Vathas, therefore, is a historical document, showing how a Cretan painter of the sixteenth century was able to interweave the old Byzantine inheritance with the new artistic currents of the West.