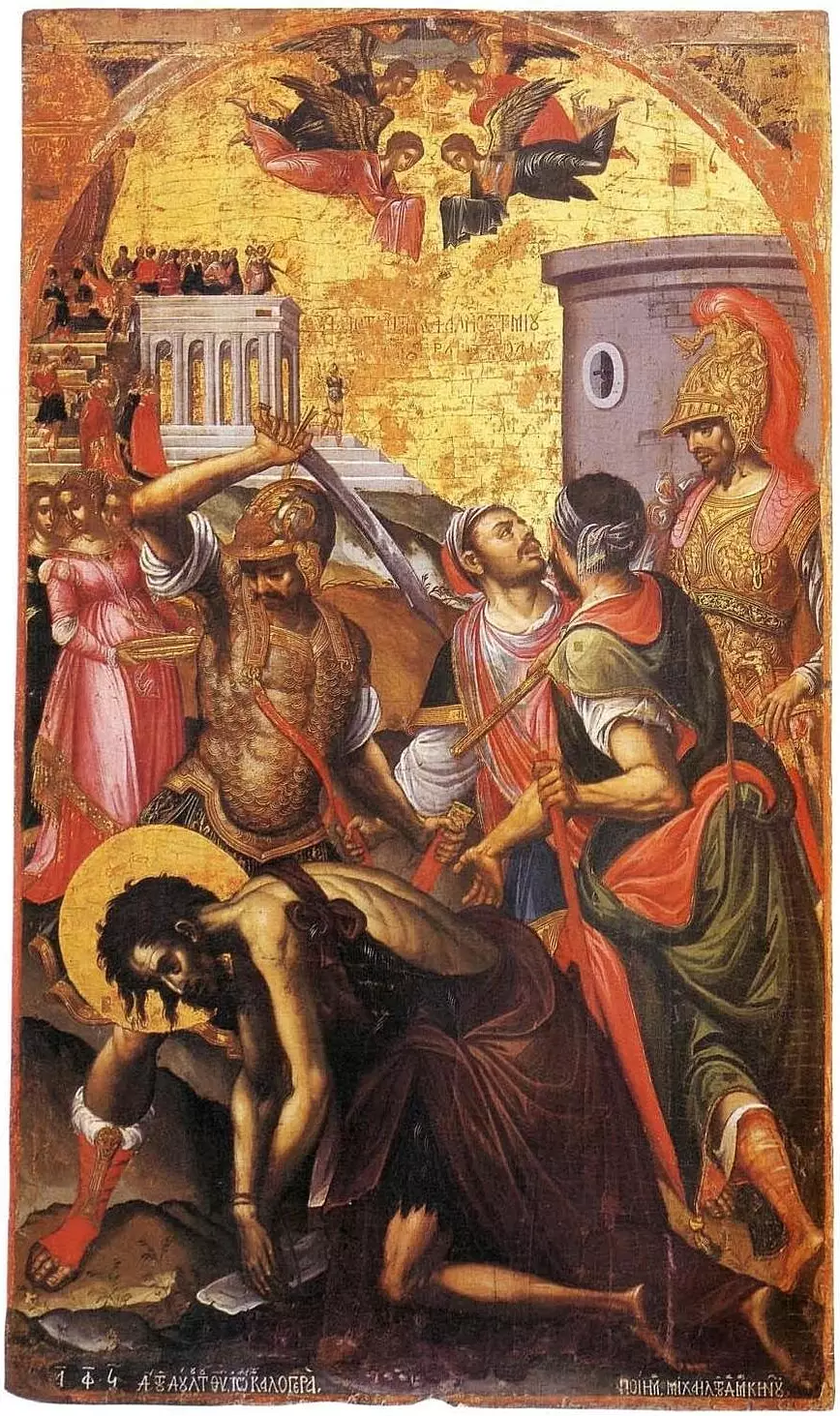

We see here not only an icon, in the usual manner. A testimony rather of art itself, a historical text, originating from Crete, but looking towards the West, namely Venice. Michael Damaskinos is, the artist, a man of the so-called Cretan School—post-Byzantine, as they say—who in the year one thousand five hundred and ninetieth (1590) made this work. «The Beheading of the Forerunner» it is called. Large it is, 165.5 by 97.5 centimetres, painted on wood with the paints of egg tempera, and now in Corfu it is housed, in the Municipal Gallery. The matter however is not simple. Damaskinos shows not one act, but an entanglement of events, almost as in an unfolding manuscript, where many scenes inhabit the same space. This composition, the multi-layered, is characteristic of his art, and indeed also of that troubled epoch, when Byzantine precision was joined with Italian passion and scenography.

A mirror of two worlds; the anatomy of the composition

How then does one read this work of art? For it is not simply viewed, but read, like a text. The narrative proceeds in many directions, and the artist forces us to move the eye up and down and to the side, so as to compose the drama.

The scene of the martyrdom

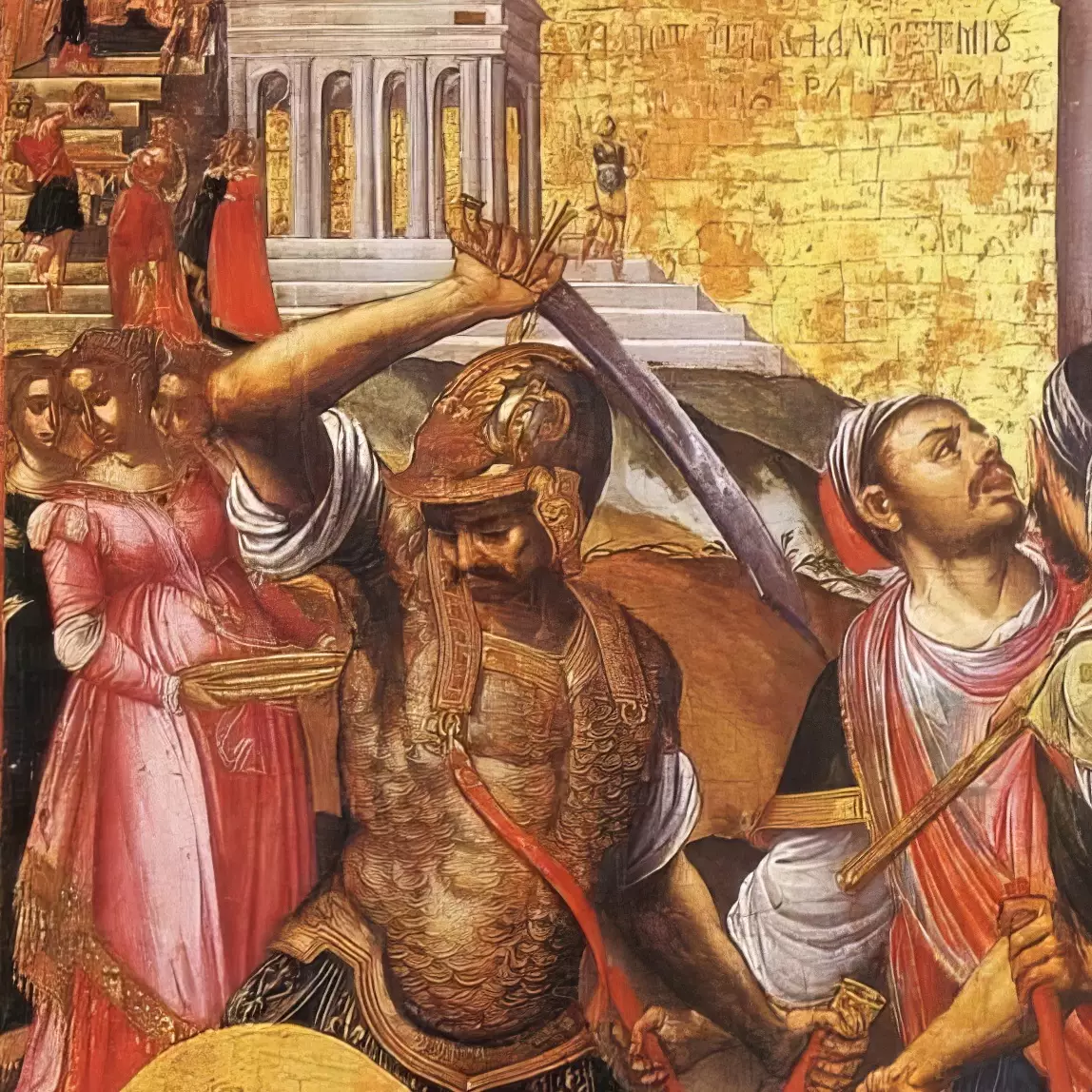

Below, on the first level, is the centre, that is. Here the Forerunner kneels. And this form is not dry or painted according to the old types of Byzantine art. It has weight. Flesh. A certain anatomical strength is apparent, which those in Italy studied—perhaps it partakes of something of Veronese? But John, this one, endures. In silence he accepts the end, having bowed his head. Above him however is the executioner, all in motion, raising the sword, ready to strike. And his armour—not Byzantine, but Roman perhaps or theatrical, such as they saw in western dramas—gleams. Beside him stands another soldier, a captain perhaps, glorying in his helmet and breastplate. This one is conversing. With some Jews, as it seems, or rulers. The politics of the matter. The worldly authority.

Time unfolding and the conflict

But the wonder is above, and to the left. The narrative does not stop at the act of the murder. Damaskinos does not treat time as one moment, but as a river. To the left, Salome. Yes, she. She turns away. She cannot look at what she requested. This is something psychological, newer, not entirely according to the old custom, which painted figures rather as symbols than as humans. And her movement, like a bridge, leads the eye into the depth. For there, another man—a soldier again—carrying the saint’s head already severed, ascends the staircase, a monumental staircase, architecturally Italian, not Judean, towards Herod who dines above on the terrace, with his court. Two, or even three, times in one panel. And above all these, at the very top, lest theology escape, the only almost purely Byzantine element: angels. They descend from heaven in clouds. To receive the soul of the martyr. This is a conflict. The old theology meets Renaissance scenography. Damaskinos stands exactly on this border, and his work testifies to the perplexity, perhaps, or the boldness, of combining the uncombinable.